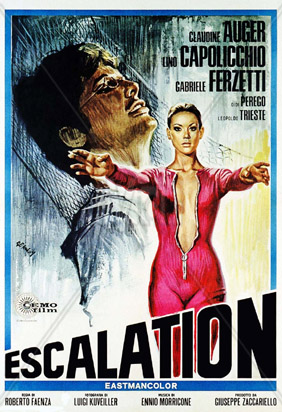

Luca Lambertenghi (Lino Capolicchio)’s life of gentle meditation amid London’s flower children and gurus is rudely shattered when his wealthy industrialist father (Gabriele Ferzetti) cuts off his allowance and forces him to work for the family olive factory in Milan. Here he shocks his colleagues with his eccentric clothes and his habit of projecting films about India on the darkened walls of his office, and is placed in an asylum. Luca escapes to Geneva and works as a baby minder but, disguised as a Buddhist monk, a female kidnapper (Didi Perego) employed by his father has little difficulty in luring him back to Milan, where his father decides to seek the help of Carla Maria Marini (Claudine Auger), an attractive industrial psychologist. Carla Maria soon has Luca madly in love with her and goes through a Buddhist marriage ceremony with him. He cuts his hair and goes daily to the office in conventional clothes; but Carla Maria refuses to consummate the marriage until he has gained control of the business. Realising that his daughter-in-law is using his son for her own selfish ends, Mr Lambertenghi reveals to Luca that her interest in him is essentially a professional one. Luca coldly poisons Carla Maria with a mushroom stew, then paints her corpse with psychedelic designs before cremating it on the beach. Later he identifies the disfigured corpse of an unknown woman as being that of his wife. And after ruthlessly forcing his father to give him control of the business he has her coffin packed in ice and buried on a city rubbish dump to the accompaniment of Negro street museums.

Dealing as it does with the development of a peace loving egalitarian into an impassive murdered and ruthless businessman, it seems likely that Escalation was intended as L’enfance d’un chef Italian style. But the comparison with Sartre proves as hollow as the more obvious one with Antonioni (for the scene changes not so much from London to Milan as from the swinging world of Blow Up to the sterile wasteland of The Red Desert.) And although the artistic and philosophical pretensions of Roberto Faenza’s first feature film seem to demand serious analysis, the disparity between intention and achievement is great enough to warrant a rather curt dismissal. Scenes like the final funeral procession display a real talent for visual composition, but Faenza seems constantly more concerned with lending a symbolic weight to his material than with what it actually signifies. Lino Capolicchio’s interpretation of the generational hero as a blabbering moron further undermines the film’s claims to seriousness. Perhaps Italian audiences are more attuned to this type of buffoon humour, but the idiom makes it hard for Anglo-Saxons to determine whether he’s supposed to be like Hamlet or just Harpo Marx. (poor)

Reviewed in Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1969.