The world of popular Italian cinema is crowded with the names of estimable filmmakers. Genuine auteurs, like Sergio Leone or Dario Argento, whose work is genuinely distinctive; or capable craftsmen such as Mario Bava, Duccio Tessari or Sergio Sollima, who dabbled in various genres, usually with some degree of distinction. Even b-movie specialists like Umberto Lenzi, Sergio Martino or Mario Caiano regularly made films which belied their low budgets and managed to look both stylish and accomplished.

However, while it’s quite appropriate that these kinds of figures are the ones that crop up during discussion of cinema all’italiana, the truth is that Italian film also provided a decent living – at least for a short while – for numerous directors who were, how shall we put it, less talented. Journeymen who could spin together a serviceable if not particularly good movie for almost nothing. They worked with meagre resources, using scripts which had usually been constructed to ape more prestigious releases as closely as possible and they shot their films in extra quick time. Their films have several distinguishing traits: a reliance on stock footage; self cannibalisation; using stuntmen as lead actors; endless time spent in which the characters walk, ride or drive around; and usually featuring a high percentage of dialogue which describes events that have already happened (or have happened off screen, because the budget didn’t stretch as far as filming it). In this wonderful domain the filmmakers were often more flamboyant than talented; individuals such as Demofilo Fidani (better known as a famous medium), Mario Gariazzo (a part-time Ufologist), Paolo Solvay (who foisted the pube-eating mutant from BEAST IN HEAT onto the public) and Aristide Massaccesi (who later, of course, became the prime exponent of Italian hardcore films). Give these guys a buck, and they’d make a film with it. Heck, they’d make two. Bad films, undoubtedly, but films nonetheless.

Although not as prolific as the aforementioned directors, Mario Moroni belongs very much in their circle. He only made two films during his long career in Italian cinema, but blth of them are cheap, nasty and rubbish. And as nobody else is deranged enough to waste their time looking at his work, it seems like an appropriate job for The WildEye.

Moroni’s name first cropped up in movie credits in 1952, when he acted as a scriptwriter on the 1952 film Dramma sul tevere. A suitably ripe melodrama, this was the story of two brothers, one virtuous (Aldo Fiorelli) and the other a delinquent (Renato Baldini). It was directed by Tanio Boccia, a quickie specialist whose name became something of a joke in Cinecitta (rushed, no budget films came to be known as Boccia jobs). In fact, Boccia wasn’t bad at what he did. He never made classics, but his films were efficient enough for them to do well in the provincial cinemas and in export (especially to developing countries in the Middle East and South America). And the people who financed his work weren’t exactly interested in their artistic merit; they were interested in hard cash.

Boccia and Moroni formed a strong partnership, and Moroni was involved in nearly all of Boccia’s films from the late 50s onwards. Ana perdonami, made in 1953, was another melodrama, this time about a former prisoner of war (Aldo Fiorelli again) returning to Italy with a fortune but consumed with grief for his dead wife. Arriva la banda was a musicarelli (a romantic story with pop songs) about a girl (Maria Fiore) in love with a drummer (crooner Matteo Spinola), much to her father’s disapproval.

With the arrival of the 1960s, Italian popular cinema was largely driven by the thirst for peplum films; mythological and historical epics featuring heavily muscled protagonists in the style of Steve Reeves (who had starred in the film which kicked the genre off, Pietro Francisci’s Le fatiche di Ercole (57)). Never one to buck a trend, Boccia threw himself upon the craze with vigour, making seven such films between 1960 and 1966. Conqueror of the Orient (60), The Triumph of Maciste (61), Samson Against the Pirates (63), Terror of the Steppes (64), Atlas Against the Czar (64), Desert Raiders (64) and Hercules of the Desert (65) were modest, unambitous entries in the cycle, indistinguishable from the mass of similar films being produced at the time. Almost all of them featured Adriano Cellini, one of the few Italian peplum stars but who was still obliged to hide his local origins by using the Americanised pseudonym Kirk Morris. During the course of these films, Moroni also extended his role, acting not only as a scriptwriter but also as an assistant or second unit director for Boccia, gaining valuable experience of working on a film set in the process.

After Agente X 1-7 operación Océano, an early and long forgotten eurospy film starring Lang Jeffries, the partnership between Moroni and Boccia seemed to dissolve. Boccia was still making films, but Moroni didn’t have any involvement with them (or at least he wasn’t credited with having any involvement with them). What he was up to during the second half of the 1960s is unknown, possibly he was working in advertising or in the nascent television industry. Whatever the case, he reappeared out of nowhere in 1971 with his first film proper, the Spaghetti Western Mallory Must Not Die.

MALLORY MUST NOT DIE

Robert Woods (Larry Mallory), Gabriella Giorgelli (Cora Ambler), Teodoro Corrà (Bart Ambler), Renato Baldini (Col. Todd Hasper), Renato Malavasi (Doctor), Artemio Antonini (Block Stone), Mario Dardanelli, Attilio Marra, Fulvio Mingozzi, Renato Mazzieri, Carla Mancini (Maria), Alessandro Perrella

Uncredited (according to IMDB): Antonio Basile (Jack)

Spaghetti Westerns had been hugely popular in the late 1960s, during which period they had been virtually guaranteed to make a healthy profit, but by the early seventies the audiences had become bored with the repetitive plots and increasingly shoddy production values, turning instead to poliziotteschi and gialli; films with a contemporary setting which seemed more attuned to the troubled times. Those that were still being made had increasingly reduced budgets, and the filmmakers who really represented this period of the genre weren’t so much tthe Sergios Leone and Corbucci as the aforementioned Demofilo Fidani and Paolo Solvay, cheapjack specialists who managed to make films, but little more.

By 1971, as well as it being the heyday of the no-budget production, the genre also experienced a transition, moving from a generally serious (if occasionally light-hearted) format into more comical territory. If people weren’t so interested in the serious stuff any more – so the thinking seems to have gone – then let’s throw in some fart gags and slapstick, that’ll keep them happy! This shift had been triggered by the hugely successful Bud Spencer and Terence Hill film They Call Me Nobody, which was released in December 1970, and within a few months virtually every director working in the genre was upping the humor and partnering little and large protagonists for comic effect. In almost all cases it didn’t work. Atypically, and despite being released nearly a year after They Call Me Nobody, Mallory Must Not Die plays it admirably straight; even if it does display all the other trademark faults of the genre at the time.

Southern Colonel Todd (Renato Baldini) has made a vow: to buy back the ranch that was tricked out of his hands by the malign Bart Ambler (Teodoro Corrà) while he was away fighting. Ambler had married his sister, persuaded her to sign over all rights to the family ranch, sold it and then killed her, leaving The Colonel homeless and itching for revenge. Unfortunately he’s also been badly wounded in the war and is physically incapable of wreaking vengeance, so he hooks up with a half-breed partner, Larry Mallory (Robert Woods), to help him realise his plans. The two of them head South with a large sum of money, intending to buy back the ranch while Ambler’s out of the territory.

After settling down in a local Inn while the deal is done, they swiftly make the acquaintance of a variety of dubious characters: there’s Cora (Gabriella Giorgelli), Ambler’s sister; Carter, the trouble-averse barman; Block Stone (Artemio Antonini), a local thug; and Doc (Renato Malavisi), a respected local surgeon. The transaction goes well and once the contract of sale has been signed they set about returning the ranch to its former glory, patching it up and investing in good quality livestock. But when Ambler returns to town he’s none too happy to discover that the ranch has been sold from under him; he also has an emotional attachment to the place and was intending to buy it back. He also knows that a railway is due to be built through the area, thus increasing the value of the land exponentially, and he’s willing to do anything he can to force Mallory and the Colonel out.

Mallory Must Not Die is generally considered to be one of the very worst examples of the genre, which is a little unfair; it’s bad, but not that bad, and it’s certainly preferable to some of the utterly crappy comedy westerns that were being made at the time. Despite hinging on a familiar revenge scenario the script does have a few distinctive features. The hero is motivated for much of the film by a sense of revenge by proxy; it’s not him who’s been wronged, but his friend the Colonel (until, that is, the Colonel is bumped off). Some of the characterisation is a little more nuanced than could have been expected, with the undoubtedly villainous Ambler being driven by motivations which aren’t that different to the heroes (he’s also portrayed as being less than the standard all powerful bandit, and the townsfolk are more than capable of standing up to him despite his short temper and gun-slinging skills). There’s also a rather ludicrous but certainly unexpected climax.

It’s not without potential, in other words, but unfortunately the execution is lacking. The more interesting elements of the story are occluded by a confusing, badly constructed narrative which regularly drifts into random territory while leaving much of the background story unexplained (the historical ownership of the ranch makes no kind of sense whatsoever, rendering the cause of the feud between Ambler and Todd incoherent). The cinematography by Mario Vulpiani – who worked on a number of prestigious films including Valentino Orsini’s L’amante dell’orsa maggiore, Marco Ferreri’s Blow Out and Damiano Damiani’s How to Kill a Judge – is undistinguished; it’s a consistently crude and ugly looking film which never manages to disguise the lack of resources with which it was made. And although the painfully apparent low budget can shoulder some of the blame, some of it must aslo be apportioned to Moroni, who seems to lack any basic understanding of how to pace a film and hasn’t the faintest idea when it comes to staging action sequences. If directed by a competent genre filmmaker such as Sergio Garrone or Paolo Bianchini, who also both traded in similar no-frills storylines, it could have been a more worthwhile affair.

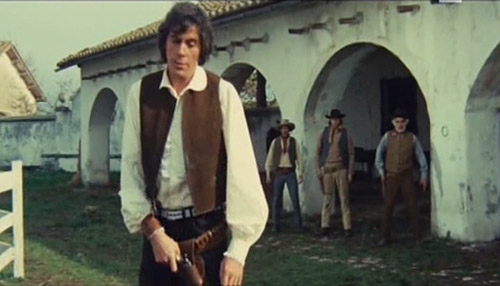

As for the cast, Teodoro Corrà, an underrated performer, does a good job as Ambler, while Robert Woods – who wasn’t above appearing in this kind of no budget nonsense at the time – sports a strange pigtail and looks a little gaunt. There’s also an unusually large role for Artemio Antonini, a stuntman who was more commonly to be found in blink-and-you’ll-miss-him parts; the fact that he has such a prominent part is probably as good a demonstration of the scant resources at hand as anything.

Unsurprisingly, Mallory Must Not Die hardly set the box office alight, although it presumably turned some kind of profit thanks to sales on the export market. Although Moroni wouldn’t make another Spaghetti Western, he did return to the genre – and to his former collaborator Tanio Boccia – as a writer on Sapevano solo uccidere, a little seen release from 1971. This was another serious-minded tale of revenge which feels slightly out of its time, with Kirk Morris as a young man out for vengeance against bloodthirsty bandito Alan Steel (aka Sergio Ciani). He also wrote a film that, unusually, wasn’t directed by Boccia, Mario Bava’s entertaining if lightweight Four Times That Night, a Rashamon style comedy told from several different characters viewpoints. In 1974, some three years after Mallory Must Not Die trickled out into Italian cinemas, he returned with a second film, Ciak… si muore.

CIAK… SI MUORE

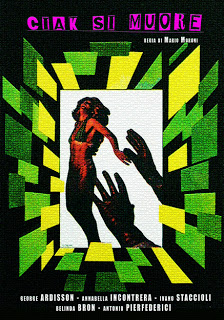

Cast: Giorgio Ardisson (Inspector Menzel), Annabella Incontrera, Ivano Staccioli (Richard Hanson, Linda’s partner), Antonio Pierfederici (Benner, a director), Belinda Bron (Fanny), Carlo Enrici (Ross, the writer), Renzo Ozzano (Sergeant Bert Malden)

While Mallory Must Not Die was a low-budget and late attempt to make a Spaghetti Western, Ciak… si muore was an equally low-budget and late attempt to make a film from another popular genre already way past its best: the giallo. Giallos – Italian thrillers named after the yellow jacketed, dime-store novels of writers like Edgar Wallace which had inspired them – had been sporadically released throughout the 1960s before entering a purple patch during the early 1970s. Following key releases such as The Sweet Body of Deborah and The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, numerous films leapt onto the trend, reusing key motifs that characterised the format to the point of tedium: a killer wearing black gloves; numerous starlets getting bumped off one by one; a weary cop with a distinctive character trait; the final revelation of the ‘unexpected’ killer, generally driven by near incomprehensible – and often pseudo psychological – motives. The genre had already outlived its welcome by 1973, at which point the number of productions dropped to a trickle, generally made by either semi-reputable film-makers with a particular connection to the format (primarily Dario Argento) or cheap-jack producers who hadn’t yet cottoned on to the fact that everyone else was more interested in sex or crime films.

While Mallory Must Not Die was a low-budget and late attempt to make a Spaghetti Western, Ciak… si muore was an equally low-budget and late attempt to make a film from another popular genre already way past its best: the giallo. Giallos – Italian thrillers named after the yellow jacketed, dime-store novels of writers like Edgar Wallace which had inspired them – had been sporadically released throughout the 1960s before entering a purple patch during the early 1970s. Following key releases such as The Sweet Body of Deborah and The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, numerous films leapt onto the trend, reusing key motifs that characterised the format to the point of tedium: a killer wearing black gloves; numerous starlets getting bumped off one by one; a weary cop with a distinctive character trait; the final revelation of the ‘unexpected’ killer, generally driven by near incomprehensible – and often pseudo psychological – motives. The genre had already outlived its welcome by 1973, at which point the number of productions dropped to a trickle, generally made by either semi-reputable film-makers with a particular connection to the format (primarily Dario Argento) or cheap-jack producers who hadn’t yet cottoned on to the fact that everyone else was more interested in sex or crime films.

Perhaps taking its cues from Fellini’s 81/2 – okay, perhaps not – the plot centres on a group of characters making a new, low-budget opus. Benner (Antonio Pierfederici), a renowned director, is the main mover behind this ‘masterpiece’; which is based on a much-mutilated screenplay by his regular writer Ross (Carlo Enrici), who’s increasingly appalled to see his great work being reduced to a cheapjack sexy comedy. And things don’t get any better when a hysterical diva is killed on the set, murdered while filming a sequence which takes place in a car wash. Inspector Menzel (Giorgio Ardisson) is called in to investigate and, oblivious to the proto-post-modern self-referentiality at play and ignoring the fact that the entire crew seem amazingly un-phased by what’s happened, he begins drawing up a list of likely suspects. At the head of it is Hanson (Ivano Staccioli), a thuggish electrician and former associate of the dead girl, but he has a cast-iron alibi thanks to a local whore (who works in the back room of a grotty café).

Before long another actress is bumped off, strangled in her dressing room just before she can pass on a vital bit of information to the Inspector; then another, bashed around the head while taking a shower and then finished off while comatose in hospital. In the meantime Benner is cooking up an insane climax to the film including a veritable fight to the death between good and evil, Ross is looking ever more dispirited and the Inspector seems far more interested in having a fling with actress Lucia (Annabella Incontrera) that doing any kind of detective work. But amongst all this, who could the real killer be?

To be blunt, Ciak… si muore is not a very good film. It’s all very predictable and uninspired, not to mention hindered by some poor cinematography from lower-than-low budget specialist Giovanni Raffaldi and a terrible, and terribly inappropriate, soundtrack from Aldo Buonocore (who seems to have been inspired by silent movies rather than the music of his own era). As with Mallory Must Not Die, the lack of filmmaking finesse isn’t helped at all by the extremely low budget, which leads to much of the film being shot in run down offices or studio sets and featuring talking heads discussing the finer points of the plot. The pacing is erratic, to say the least, with the running time padded out by an unlikely love affair between the Inspector and Lucia (which is subsequently forgotten about), and Moroni seems to have little ability at shooting action sequences, all of which end up being stodgy and confused.

But… if accepted as a runt among the giallo litter, it’s not without its own moments of charm; most of which, it must be said, seem to be accidental. The plot, despite the disappearing red-herrings and other summary diversions, does kind of keep on track and has a certain simple effectiveness. Perhaps this was thanks to the involvement of Roberto Mauri, another low-budget specialist and occasionally effective director in his own right (and who could quite frankly have done a much better job with the raw materials at hand). Then there are some jaw-dropping sequences which come out of leftfield: a protracted dance scene in which Belinda Bron gyrates around in just a bikini during a horrid looking ‘party’; the climax, in which several people dressed in Diabolik costumes – one of whom is the killer – chase numerous bikini wearing starlets around an extremely crimson theatre (no, it doesn’t make any sense whatsoever, but it’s worth the price of admission in itself).

Further kudos come from Moroni’s surprisingly effective documentation of the art of low-budget filmmaking (although, worryingly, it’s implied that the film-within-a-film here is a reputable production). With its dingy studios, precious directors, downtrodden writers always on hand to revise a script, bitchy starlets and assorted dubious hangers on, it rings fairly true as a representation of what it was actually like to make these kinds of films. There’s an amusing scene set in a quarry, where the entire crew consists of about twenty people, a decrepit caravan and a film camera; which must have been just about what it was like filming Mallory Must Not Die. There’s also a reference to Antonioni’s Blow Up (by way of Argento), with a vital clue captured on film but not understood, although this ends up falling off the radar of the scriptwriters, who make no further mention of it after the half hour mark.

As for the actors, Antonio Pierfederici is good fun as the flamboyant Benner, while Ardisson makes a suitably bemused foil (‘You want me to believe you don’t know what you’re doing?’, he exclaims, when presented with Benner’s explanation of the art of improvisation). Familiar villain Ivano Staccioli ends up having a surprisingly heroic role and giallo regular Annabella Incontrera has a glorified cameo. It’s bad, for sure, but that doesn’t mean it’s unenjoyable in its own cack-handed fashion.

Unfortunately, it would also prove to be Moroni’s last film as a director. He did receive one further film credit, as a writer on a virtually unseen Tanio Broccia war movie from 1981 called La guerra sul fronte Est. It’s a shame this is apparently unavailable as it sounds rather interesting: a couple of Italian soldiers on their way to period of leave are attacked by Greek troops and forced to take refuge in an old mine with a motley group of other survivors. Renato De Carmine and Roberto Maldera starred. This also proved to be Tanio Boccia’s last film: he died in 1982, just after it’s release.

During the late 1970s and early 80s, Moroni also worked occasionally in television. Information about Italian TV is sketchy, but he is known to have directed two mini series. Il povero soldato, from 1978

Leave a Reply