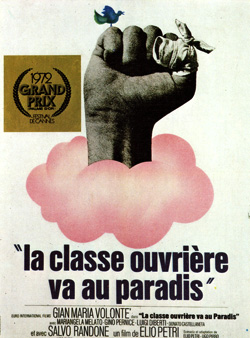

Aka La classe ouvrière va au Paradis (Fr), La classe operaia va in paradiso (It)

Italy

1972

A Euro International Films production

Director: Elio Petri

Story & screenplay: Elio Petri, Ugo Pirro

Cinematography: Luigi Kuveiller {Eastmancolor}

Music: Ennio Morricone, conducted by Bruno Nicolai and featuring Alessandro Alessandroni’s I Cantori Moderni

Editor: Ruggero Mastroianni

Art director: Dante Ferretti

Cameraman: Ubaldo Terzano

Release dates & running times: Italy (17/09/71, 111 mins), France (31/05/72)

Filmed:

Italian takings:

Cast: Gian Maria Volonté (Ludovico Massa, aka Lulu), Mariangela Melato (Lidia), Mietta Albertini (Adalgisa), Salvo Randone (Militina), Gino Pernice (the union politician), Luigi Diberti (Bassi), Renata Zamengo (Maria), Donato Castellanetta (‘Marx’), Federico Scrobogna (Pinuccio), Giuseppe Fortis (Valli, the factory manager), Adriano Amidei Migliano (a technician), Ezio Marano (the chronometer technician), Luigi Uzzo, Corrado Solari (a new recruit), Carla Mancina, Guerrino Crivello, Antonio Mangano, Lorenzo Magnolia, Giovanni Bignamini, Eugenio Fatti, Flavio Bucci (a factory worker), Renzo Varallo, Marina Rossi, Orazio Stracuzzi, Alberto Fogliani

Volonté and Petri joined forces again for 1971’s The Working Class Goes to Heaven and, impressively, they managed to concoct something that was even more hysterical than Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion. Volonté stars as Lulu, a model employee in a large, North Italian factory. His dedication to the job antagonizes his fellow workers, especially when his efficiency causes the management to raise their production targets (without, of course, a corresponding rise in pay). He begins, however, to question whether his commitment is a good thing: his family life is a mess (not much helped by the fact that he never speaks without shouting), he’s impotent and his friend Militina (Salvo Randone) has ended up in a loony bin. Things come to a head when he loses a finger in the machinery whilst maniacally trying to achieve his self-imposed quota.

Unhappy with the performance of his union in protecting his rights, he falls in with the anarchist students who make a habit of picketing the factory, becomes caught up in riots and loses his job. This causes him to have a mini nervous breakdown and, in the meantime, his plight becomes something of a symbol to the rest of the workers. Things end on a guardedly optimistic note when the union manages to win his re-employment and his relationship with his girlfriend and stepson takes a cautious upturn.

Heavy stuff, and in the hands of some directors it could all have become a lumpen mess; Petri, however, is such a charismatic filmmaker that he manages to make it all more watchable than might have been expected. It’s angry, for sure, but largely manages to seem less proselytizing (and patronizing) than a lot of self-proclaimed political cinema. To a large degree this is due to the fact that it is, on several occasions, laugh out loud funny. Particular instances that come to mind include a ridiculous psychologist (‘What do I remind you of?’, ‘A cock’), and a hilarious sequence in which Lulu and a factory girl make love in his clapped out Fiat Uno (which aptly demonstrates the difficulties involved when shagging in seventies motors). As the alternative comedians made clear in the eighties, trying to put across a social message is often most effective when done under the cloak of humour; sorting through the accumulated junk in his flat (‘Magic Moments’ gas powered candles!) Lulu is reduced to exclaiming ‘Who makes this stuff?’ repeatedly, as perfect a criticism of consumerism as you can get.

The factory is portrayed as a bleak concentration camp of a place, constantly surrounded by snow, fenced in, guarded and almost featureless. No one who works there actually knows what they are making – is it components for an engine? The conditions aren’t too dissimilar to those of the workhouse, only in this case the reward is money (which is spent on food and lodging) rather than, err, food and lodging. Petri’s sympathies obviously lie with the students who argue that this kind of freedom is illusory, a happy convenience that enables the upper to exploit the lower class. On the other hand, these students are also shown to be annoyingly lacking in sympathy for the individual – they’re so bound up in pursuing causes they actually forget what the cause means.

Ugo Pirro explains: “Before writing The Working Class Goes to Heaven, we did a lot of research. Every morning we’d go to the gates of Fatme and we’d film the procession of workers going in and conduct interviews with the students. We did dozens of interviews; with workers, trade unionists, the company directors. The biggest problem for the film was finding the factory, as no one wanted to let us shoot in one. Eventually we discovered an elevator factory which was in crisis and had been occupied by the workers, but they didn’t have an assembly line. So they helped us construct one!”

Armed with the great cinematography of Luigi Kuveiller, Petri makes tremendous use of sets and art direction, and has the particular habit of shooting actors in front of bizarre paintings (as is the case with the final freeze-frame here). Morricone’s dissonant soundtrack is not entirely disimilar to the his contribution to crime films such as Sollima’s Violent City (Città violenta, 70) and Lizzani’s Wake Up and Kill.

At the centre of it all, though, lies Volonté’s performance. It’s easy to forget just how intense a performer he was; dressed up in hideous jumpers and kipper ties he comes across as an unholy cross between David Jason in Open All Hours and Dennis Hopper. Strangely enough, for a symbol of the proletariat his character is never actually very likeable; he’s venal, selfish and hostile to virtually everything and anybody. That you can even tolerate the guy is something of an acting triumph.

Petri certainly saw the film as a continuation of themes that had been long present in his work: “The initial idea was to show how in this society it’s impossible to live in isolation. Also, how the conflict between existential and productivity needs, which you can also see as far back as I giorni contatti. Another of the things that has always motivated me is the desire to break away from the neo-realist canon. In those days, you either respected or rebelled against this canon, and it acted as a kid of expressive imprisonment. They thought you should always ‘respect’ reality, whereas I believed reality was a matter of interpretation, made up of symbols and metaphors and never quite working to plan or systematically.”