In view of its hybrid origins it seems highly appropriate that one of the central ideas in They Came to Rob Las Vegas should be the impersonality of life in the space age, where the old style gangster lethally learns that violence and bravado are inadequate weapons in a technologically sophisticated world, and both master criminal and investigator must resort to a computer to direct their operations. Not that Isasi has produced an ideas film – anything but – for the expositiory comments made by Tony (Gary Lockwood) and his friends about the age of George Raft-style gangsters being over are illustrated in a series of starkly effective action sequences: Gino (Jean Servais) and his associates finding their bazookas are as ineffective as popguns against the security truck with its two way TV control, periscope and built in machine gun; Tony and his firends unable to open the impregnable truck even after they’ve hijacked it in an almost surrealist ambush in the empty desert, where their flam throwers belch forth amid the heat haze of the apparently unpeopled dunes. Superbly executed, the details of the robbery seem at first to constitute an homage to human ingenuity; yet what Isasi in fact demonstrates is that man is the last fallible element in the mechanical age, no match for his infallible inventions (Skorsky (Lee J. Cobb) has to consult the computer in order to discover that his mistress is unfaithful to him!) The films opening sequences, set on the freeways of San Francisco and later on the Los Angeles clover leaf, reveal man’s insignificance in the face of modern machinery (radiong his report on the capture of Gino’s gang, a policeman phlegmatically remarks ‘no survivors expected’, the blood and bodies on the highway representing little more than a hazard to traffic circulation

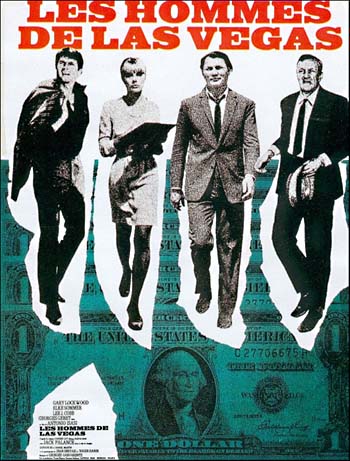

But if man is dwarfed in civilisation, he’s unlikely to feel any more at ease in nature. The empty Nevada deserts where Isasi situates most of the action are as threatening in their huge impersonality as the neon-flooded gambling halls or the glistening steel of the room that houses the computer, appropriately known as ‘Big Brother’. Isasi, a native Spaniard, has captured two of modern America’s many faces: the huge expanses of untamed natures; and the modern city, all traffic and no centre, where nature has been totally replaced by constructions of concrete and steel. Both provide a hostile environment – a fact emphasised by the camerawork, which avoids pans and travelling shots, preferring to show characters in long shot or from the air, forever dwarved by their setting. And if the English dubbing is occassionally obviously, there are ample compensations in the performances of Gary Lockwood as the precise and hang-loose criminal and Jack Palance as the patient, blundering investigator. Though even they must tke second place to the action and locations.

Review from Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1969.

Comment: What an interesting review, written by Jan Francis, who later went on to edit the Monthly Film Bulletin. It neatly sums up one of the less highlighted aspects of 60s cinema (and the Eurospy and caper genres in particular): the developing relationship between people and technology. Many of these films feature futuristic gadgets, hi-tech underground bases and vaguely sci-fi style plots. In most of them the carefully considered schemes / heists / masterplans are undermined by human frailties and in-fighting. Technology is a positive thing – on the whole – but it can be used to commit evil deeds and it simply highlights the unpredictability of the people who use it. The fact that the review is so positive is also interesting: I thought that just about all Italian and Spanish action films received a bad review as a matter of course!