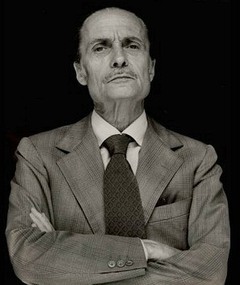

Here’s another interview with Stefano Vanzina, aka Steno [see also here]. Once again, this was translated from an old copy of the Italian newspaper L’Unita.

Here’s another interview with Stefano Vanzina, aka Steno [see also here]. Once again, this was translated from an old copy of the Italian newspaper L’Unita.

Seventy one years old and with fifty nine films to his name, Steno has been underestimated, despised, reevaluated, overestimated. At a point in which ye has to balance his life, stating that he dedicates himself simultaneously to the sublime and the essential, Steno continues to work with as much force as he did in the old days, when he wrote stories or sketches for Marc’Aurelio, or when he co-directed in tandem with Mario Monicelli.

“What can I do, they telephone me continuously,” says Steno, who has in the last twelve months shot Doppio delitto and Piedone l’africano and is currently planning another film with Alberto Sordi. “And I don’t want to be like the old man who slams the door in the face of new ways. Nonetheless, I believe that the young need to heed what has gone before, in the sense that through all those years, they are pieces in the puzzle. I believe also that there’s an objective need to change Italian cinema, because for us working in television or advertising isn’t as good for getting experience as in the United States. And mental laziness weighs heavy. Take the producers… they cry with misery, they’re always on the verge of suicide, but they have no interest in looking for new ideas.

“But it isn’t just the young or the inexperienced who are rejected by producers,” says Steno. “Even I, who has been able to work with a certain security for some time, when I tried to get them interested in the script for La polizia ringrazia they wouldn’t take me seriously. And the film, which didn’t cost much, I ended up practically producing it on my own. Certainly, it was a risk, and I often asked myself if I’d be able to involve someone like Enrico Maria Salerno, or if people would want to see a poliziesco which I’d devised, and which didn’t feature a cop who goes around slapping people in the face. As it was, it was more successful than I expected and also gave rise to the ‘poliziotto’ filone. Always you have the usual industrial crap in Italian cinema before you do a shoot, then you have to queue up in the worst possible way. It displeases me that things are like that. And I continue to sustain that it wasn’t a reactionary film.”

Steno is happy to talk, and he’s doing well. It’s no coincidence that he started out as an actor. “In 1930, I lived in a hotel with my family which we owned and which was frequented by actors. When I was thirteen I very much liked being the centre of attention and started out by reciting futuristic poetry, stuff like ‘bim, bam, bum, crash, splash, patapum.’ Well, one girl took me to do this in the alcove at De Bono, among the black marketeers, and the director Febo Afari cast me in his film of Pinocchio. I met him in my rooms and all the street boys took me for his pretty boy. Nonetheless, that’s how I got into Italian cinema, before moving onto Marc’Aurelio with all the others. Like Fellini, for instance, who came into the office to show us his drawings.”

“During the war, I was in Naples with the Americans. I played the voice of Il Duce in a radio program called Stella bianca. Then when I returned to Rome I happened into the magazines. Il suo carello was produced by De Laurentiis and directed by Renato Castellani, that was something out of the ordinary. We couldn’t believe it, but it wasn’t a joke. After that I did Il gagman for Macario… and then in 49 I co-directed Al diablo la celebrita with Monicelli.”

How was it working with another director?

“It was like a sexual thing… we laughed at the same stuff, and it never occurred to us to think who was better or best. I was more occupied with the actors, Mario loved being behind the movie camera. At the time we spent a lot of time together, he was easier to see. Physically, I mean. Even though he continues to repeat that he’s nothing more than an artisan, Mario continues to remain faithful to his vision. I, on the other hand, am not a fan of flashy aesthetics. You could say that I don’t feel the movie cameras, to quote Chaplin.”

Of Toto, Steno directed the great Neapolitan actor fourteen times. “Doing films with Toto was a sufferance. We always depended on his invention, and everything else had to revolve around him. He collaborated instinctively, and would only work in the afternoons because he said that the mornings weren’t good for making people laugh, stealing a line from Oliver Hardy. Toto was an extremely egocentric type. When we took him the script of Guardie e ladri his response was: “Very nice, but what do I do?” But he’d tease Aldo Fabrizi. It made him laugh to make mistakes, with his found improvisations. He’d say profanities that weren’t submissable on the screen, which made it all difficult. But he was a marvel. These ‘mostri’, they always gave their all, which makes it difficult now to settle for some of the anodyne performances of some of the actors in circulation now. Certainly, they needed reining in, as you’d expect from avavspettacolo performers, or they risked unbalancing the film. Apart from anything else, even the neo-realists borrowed from avanspettacolo, just think of Fabrizi and Magnani in Rosselini’s Roma citta aperta.

And Alberto Sordi?

Alberto Sordi gifted the best episode of Un giorno in pretura to me. But it wasn’t easy to convince the producers, because when they read in the script that the actor was nude they said: “Surely you’re mad, Sordi nude? Put in Walter Chiari instead, Sordi will disgust everyone!”

Nonetheless, they were very productive, these old school producers…

“They were mad. All of them. The honourable Barattolo, who always had Francesca Bertini at his side, he had a pedal under his desk which he could ring the telephone with and get rid of pests. Fortunato Misiano, who couldn’t understand there was another world apart from cinema, one day he said to me: “I found this great story, I was sent it to read, but I didn’t realise this son of a bitch had taken it from a book.”

“But now,” concludes the director, “there isn’t the same spirit and we live without knowing whether things will succeed. In order to do a film they want it to be some kind of abstruse co-production, or you need to wait years for the actors to become available. But I continue to say that cinema isn’t in crisis, just the way you make a film for the audience. In Italy, cinema doesn’t describe the setting, doesn’t talk to people. Any yet any film is a reflection of the lives and humour of a culture, because the books arrive too late. “