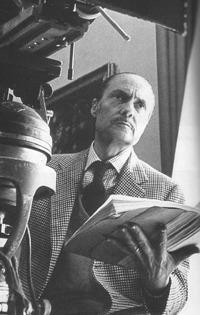

Here’s an interview with Stefano Vanzina, aka Steno, the director of numerous Italian comedy films from the 1950s onwards. He also made a couple of effective straight films, including one of my very favourite – and hugely influential – poliziotteschi, From the Police with Thanks. The interview was published in an ancient copy of Italian newspaper L’Unita and is translated by me (apologies for any errors!)

He’s the founder of the now famous Vanzina cinema family (his sons are Carlo and Enrico), and Stefano Vanzina, perhaps better known as Steno, loves to talk about them. What they make of their careers, we’ll wait and see. At 68 years old, having directed 75 and written nobody knows quite how many films, he says that he doesn’t now feel as if he’s retired. Nonetheless, recent years have seen a mood of celebration and critical re-evaluation of his career. He’s now considered to be a true master of Italian comedy cinema who touched all his films with a kind of honest craftsmanship. Over the years he has worked with such icons as Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, Alberto Sordi and naturally Toto.

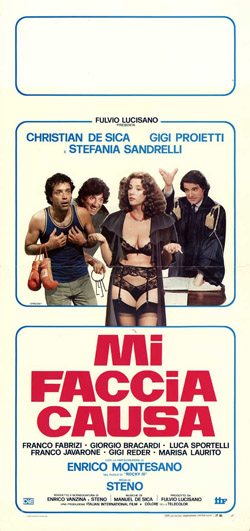

Small in stature, thin, nervous and pragmatic, with a slightly old fashioned moustache that matches the colour of his slicked back hair, Steno is still at work. He has just released Mi faccia causa, which he considers a remake of his celebrated Un giorno in pretura, and he’s already thinking about a film for TV he’s due to start shooting in the Spring: I clan, a story about the mafia written with De Caro. He’s tireless. He says that completing a film nowadays is much more difficult than it used to be, he laments the laziness of producers and the tastes of the public, but then acknowledges that for him things continue to go well. Like his films or not (and his last film, Mani di fata, was extremely mediocre), Steno continues to sail peacefully through a crisis in Italian cinema, perhaps squeezing his eyes in the face of fashion or microscopic changes in costumes. As in the episode of Sandrelli in Mi faccia causa, this tells of a model and worker who, in opposition to the absenteeism and degeneration, ends up taking her work back to the bedroom.

Q: Steno, is it the case that your son, Enrico, an avowed cinephile, teased you with the idea of doing this remake?

What? You think I’m so narcissistic that I pay homage to myself? No, the idea clicked while I was chatting with producer Fulvio Lucisano. We were due to do another film, but there were problems. Then I said: “Why don’t we remake Un giorno in pretura?” “Ok,” replied Lucisano, without giving me the chance to think about it any deeper.”

Q: Of course you updated the situation and modernised the characters. But do you think that despite these changes, deep down it remains the same film as it was thirty years ago.

Have you never been in a magistrate’s court? Spend a day at one and then ask me the same question. Certainly we changed the locations (in 1954 the magistrates courts were in via del Governo Vecchio, the palazzo which later became the headquarters of the feminists.) But the stories have stayed the same: little scams, bizarre accusations, abusive fabrications.

Q: Yes but then it was Alberto Sordi who played the character Nando Moriconi in the funny episode ‘Maranella’, there was Peppino de Filippo in good form. It was, if you’ll forgive me, a slightly richer cast.

Ah, Sordi. Today that episode is considered to be a cult movie, but what would you think if I were to tell you that the producers back then didn’t want him. For Gianni Hecht and Carlo Ponti it was a vulgar sketch, they said that having Sordi in the nude wouldn’t make people laugh; they even tried to make me cast Walter Chiari instead, because he was better looking. But we made the right choice.

Q: We’ve already talked a bit about Sordi. You made five films with him, the last being Anastasia nio fratello, so you must have good memories of him.

Alberto was, at that time, around the beginning of the fifties, a continuous explosion of jokes and gags. There was nothing that could stop him. I very much liked the fact that each time I saw him I’d cry with laughter, as in the case of Piccola poste, where he tortured beyond belief those poor old men. Remember? Sordi knew how to hold his own against anyone, even Toto. In Toto e I re di Roma Toto understood well that he had opposite him a great actor, so in one scene he improvised a series of sneezes in order to get a laugh. Sordi, with the minimum of self-doubt, held his own with some by-play that was even more amusing.

Q: Going back, Steno was born to be a writer or a director?

The one and the other. I began working in the cinema together with Mario Monicelli, writing about six or seven screenplays a year with him. But the transition to becoming a director happened quickly. In reality I began, artistically, by writing for Marco Aurelio. My friends there were Metz, Marchesi, Maccari, Zavattini, Age and Scarpelli… the first time that Fellini came looking for work there it was me who received him. He was a boy; he bought with him a briefcase full of cartoon. He tipped them out on the table and I immediately realised that this youngster was something special. They looked like they were designed by Da Grosz

Q: You have said before (in L’avventurosa storia del cinema Italiano) that Marco Aurelio and Bertoldo were where all the postwar directors started out.

Yes, that’s right. Then – and I’m speaking about the end of the thirties – it wasn’t easy to break into cinema. It was a closed world, privileged, where the earnings were good. As an assistant director I’d be able to stay in hotels which today I can only dream about. It was thanks to Metz that I was able to get my break as a ‘gagman’ among the group of writers of Mattoli’s Imputanto, alzatevi! The film turned out to be a crazy success, equaling the takings of Greta Garbo and Clark Gable films, who were the icons of the time. So Mattoli also hired me to work on the screenplay for his following film, Lo vedi come sei? with Macario, and he also took me on as an assistant director. I was made.

Q: And do you have anything to say about Orson Welles?

Excuse me, but why don’t we talk about today. You are really all the same you young critics. It was Ponti who came up with the idea for L’uomo, la bestia e la virtu, perhaps because doing Pirandello gave the potential to engage great actors such as Welles. But in reality the film didn’t work. Welles accepted the contract for the money; he didn’t give a damn about the film. But on set he was always a perfect gentleman. He’s one of those directors who, when they work as an actor for another director, are able to behave like a guest rather than a master.

Q: Returning to today, now. Is it true that you reproached your son Enrico for doing screenplays that weren’t steely enough?

No, that’s not true. But, talking about Rene Clair, I’m now convinced that the director is the defendant of the scriptwriter. He needs to turn to the scriptwriter to write, to come up with the stories and ideas. Italian cinema is in crisis because for many years producers have believed that they can earn millions by merely putting together two comics and having them joke. The story comes afterwards. Of course, you never want to direct a film in opposition to your actor, but then you have to guide them, go along with them to a degree while curbing their worst excesses.

Q: What else has changed in making comedies over the years?

Nothing, the avant-garde doesn’t exist in comedy. You can aim your farces at young people or make them for video, but the rules don’t change. It’s all to do with rhythm, the way the jokes are paced. Take Benigni, even he, at the end of the day, is influenced by Toto, Chaplin and the Marx brothers.

Q: One last question, do you have any regrets?

No, I don’t think so. I’m perhaps a little tired of doing comic films because – as the producers say – people can only laugh so much. I know how to make other films as well. For that reason I was really happy when a Roman critic, Cosulich, at the time of La polizia ringrazia, cited among all my possible inspirations Fritz Lang. He couldn’t have known it, but M has always been one of my favourite films.

Comments