For some reason, Elio Petri is a filmmaker who seems to have slipped off the cultural (and counter-cultural) radar. To the art-house crowd, Italian cinema is composed of the giants – Rossellini, Visconti, Bertolucci, Pasolini – with very little else getting a worthwhile look in. Among those with a taste for more exploitative fare, you’re more likely to hear discussion of Batzella’s The Devils Wedding Night (Il pleniluno delle virgini, 73) or Bianchi’s Strip Nude for your Killer (Nude per l’assassino, 75) than Property is No Longer Theft (La proprietà non è più un furto, 73).

Some have argued that this is because of repression; Petri was the most political of directors, and his work couldn’t fail but antagonize the authorities in his own homeland. This is probably a conspiracy too far, though, with it being more likely that the very ‘unclassifiability’ of his films makes them more difficult to pigeonhole within a traditional critical perspective. Too populist for high culture, too arty for low, he sits with a small group of mavericks – Valerio Zurlini, Carlo Lizzani, Giuliano Montaldo, Damiano Damiani – who attempted to use genre frameworks as a means of conveying their socio-political ideologies. It could also be something to do with his comparatively early death, in 1982 – at the age of 53 – of cancer, which robbed him of the opportunity to become one of the elder statesmen of Italian cinema.

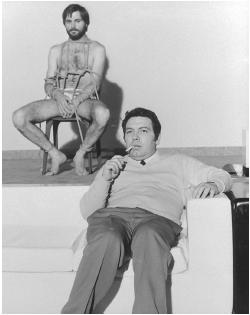

This relative obscurity is a shame, as his work includes much to interest the casual observer, the cult fanatic and the traditional cineaste. Oscar nominated for best screenplay in 1972 for Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto, 70), Golden Palm winner at Cannes for The Working Class Goes to Heaven (La classe operaia va in paradise, 71), he regularly scored highly on the festival circuit at the time. Beyond this, however, his work includes an effective giallo (We Still Kill the Old Way (A ciascuno il suo, 67)), a ghost story (A Quiet Place in the Country (Un tranquillo posto di campagna, 69)) and a number of science fiction pieces (The Tenth Victim (La decimal vittima, 65), Todo Modo (76)). That so little of this is available to date on DVD is frankly criminal, and it can only be hoped that the situation is remedied before too long.

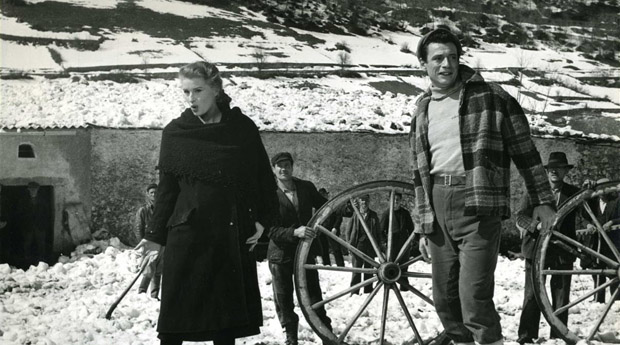

Born Eraclio Petri on January 29th, 1929 in Rome, he grew up in the traditional working–class area of the city, where his father worked as a coppersmith. He became a committed communist at an early age, which led to his expulsion from Catholic school, and soon found work as a cultural coordinator for the youth arm of the Communist Party. Like many left-wing Italians he found it difficult to reconcile his socialist beliefs with the reality of Stalin’s Soviet Union, and he left the party after the Hungarian uprising in 1956. By this time he’d made friends with Gianni Puccini(1) (who would go on to make Ballata da un miliardo (67) and The Fury of Johnny Kid (Dove si spara di più, 69)), who introduced him to Giuseppe De Santis, the respected director of neo-realist classic Bitter Rice (Riso amoro, 49). Petri was soon acting as a scriptwriter and assistant to De Santis on Giorni d’amore (54) and Uomini e lupi (56), an experience which went on to have a profound influence upon his later directorial career.

The filmography of Elio Petri:

- The Assassin (61)

- His Days Are Numbered (62)

- Nudi per vivere [documentary] (63)

- The Teacher from Vigevano (63)

- High Infidelity [episode ‘Peccato nel pomeriggio] (64)

- L’Italia con Togliatti [documentary short] (64)

- The 10th Victim (65)

- We Still Kill the Old Way (67)

- A Quiet Place in the Country (68)

- Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (70)

- Documenti su Giuseppe Pinelli [Documentary short, segment ‘Tre ipotesi sulla morte di Guseppe Pinelli’] (70)

- Lulu the Tool (71)

- Property Is No Longer a Theft (73)

- Todo Modo (76)

- Le mani sporche [TV mini series] (78)

- Good News (79)

(1) Born on the 19th November 1914 in Milan, Gianni Puccini followed in his father Mario’s footsteps by becoming a scriptwriter, working on Visconti’s Ossessione (43), De Santis’ Bitter Rice (Riso amaro, 49) and numerous other reputable films throughout the forties and fifties. His directorial career was rather more varied, with his main output being middlebrow comedies like L’impiegato (60) and Amore facile (64), and he was also something of a specialist in contributions for the anthology films that were popular in the late 50s and early 60s (Love in 4 Dimensions (Amore in Quattro dimensioni, 64), The Double Bed (Le lit à deux places, 65)). Towards the end of his career his work became more varied: I sette fratelli Cervi (67) was a much admired political war film, Ballata da un miliardo (67) a cheesy caper flick and The Fury of Johnny Kid (Dove si spara di più, 69) a very strange spaghetti western remake of Romeo & Juliet (complete with a leftfield ending that has to be seen to be believed). Unfortunately, just as things were starting to get really interesting he died of a heart attack on the 3rd December 1968.