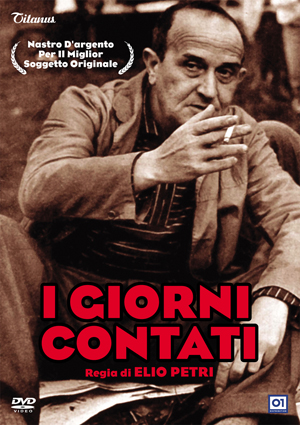

Italy

1962

A Titanus, Metro production

Director: Elio Petri

Story: Antonio Guerra, Elio Petri

Screenplay: Elio Petri, Antonio Guerra, Carlo Romano

Cinematography: Ennio Guarnieri

Music: Ivan Vandor, conducted by Pier Luigi Urbini

Editor: Ruggero Mastroianni

Art director: Giovanni Checchi

Cameraman: Luigi Bernardini

Release dates & running times: Italy (05/04/62)

Italian takings: 52.000.000 lire

Cast: Salvo Randone (Cesare Conversi), Franco Sportelli (Amilcare), Regina Bianchi (Giulia), Paolo Ferrari (Vinicio), Vittorio Caprioli (the Professor), Marcella Valeri, Angela Minervini, Renato Maddalana, Alberto Amato, Giulio Battiferri, Piero Gucaione, Vittorio Bottone, Lando Buzzanca, Aldo Pini, Vittorio Donato, Silvio Silvi, Enrico Salvatore, Egidio Porzia

Petri’s second film was I giorni contati (62), which again featured Salvo Randone. This time he plays Cesare, a plumber and widower who is riding home from work on the bus when it’s discovered that one of the passengers has died. This causes him to experience an existential crisis, and – seeing as how he’s 54 and deserves something more from his life – he decides to give up work.

He spends his days sitting around at his lodgings, playing cards with the landlord’s flighty daughter (who borrows 50,000 lire from him, ostensibly as a deposit for a new job, and blows it all on a horrible wig). He goes to the beach, where his friends think that he’s drowned (he’s wandered off to watch the youngsters groove away to terrible music in a beach hut). He goes for walks in the park (which, anticipating Petri’s final film Good News (Buone notizie, 79), is covered with litter and full of people snogging). He goes to the countryside to visit the village he was born in (and discovers his old friend to be a depressed alcoholic), and finally attempts to rekindle his romance with an old flame, Giulia (Regina Bianchi), who frankly wants nothing to do with him.

Eventually, of course, his money runs out. Discovering that he won’t be able to collect his pension until he’s sixty, he falls in with a group of fraudsters, who persuade him to take part in a scam that will net him a cool two million. He is to have his arm broken and pretend to have been hit by a car, therefore enabling him to claim recompense from the insurance company…

I giorni contati is the story of a ‘little man’ who knows that there’s more to life but doesn’t know quite where to find it. Actually written before The Assasin, again with Tonino Guerra, it was inspired by Petri’s father, who similarly gave up his job (as a coppersmith) in his mid fifties. “At that time,” Petri commented, “it was quite a novel film, for instance in what it says about – or rather against – work, about the divisions between time for living and time for working in a time when productivity was seen as being the category prerogative. The protagonist suffers because he discovers that work has stolen his life, that he hasn’t actually been living at all.”

Petri hadn’t quite cemented his flamboyant, surrealist style here, although there are some very memorable moments. Chief among these is the sequence in which Cesare is about to have his arm broken by a Neanderthal thug; a great example of how to build up the anticipation of something horrible rather than actually showing it. It’s also a concise demonstration of why, if you insist upon having you arm smashed to pieces, you shouldn’t ask someone to do it who has more tattoos than brain cells. There’s also much evidence of the director’s trademark interest in objects of art or, rather, framing his characters against objects of art.

Salvo Randone is very good in the lead role. A very talented comic actor, he has the kind of weather-beaten face that you just can’t help but liking, and manages to ride from the whimsical first half of the film to the much darker second without any problems. Working since 1943, he was obviously a favourite of Petri, going on to appear in important roles in virtually all of the director’s films (4).

Petri explained: “When I first suggested the film to [Goffredo] Lombardo I had a list of three names to play the protagonist: Toto, Jean Gabin and Randone. And he chose Randone because, obviously, he cost the least. [Amedeo] Nazzari was also mentioned, but nothing came of it. Randone was a cultured theatre actor I’d discovered, and his selection was felicitious because, to the contrary of what was said by some of the critics – the contrast between the proletarian character and the bourgouies actor was very effective. He didn’t play the character in the usual way for Italian films, but as someone in the grip of a great anguish. And this was perhaps the anguish of a bourgouies person putting themselves in the place of a working class person. Moreover, Randone had this fasinating ambiguity – he was bourgeouis but Sicilian – which was almost Pirandelloish. He could be sweet but rough, isolated and pessimistic. It pleased me very much that he didn’t treat this second class citizen in the traditional naturalistic, realistic fashion because the workeers also have the neuroses, their divisons, their dreams and their prejudices.”

There’s also a small role for Lando Buzzanca, who went on to become a phenomenally popular comedian and who, for once, manages to avoid both mugging and pratfalling for his entire performance, which must stand as some kind of record.

(4) A successful theatre actor, Randone appeared in the occasional film throughout the 1950s, but it was in Petri’s films that he first made a serious impact on the big screen. With his slightly downtrodden features, he was perfect at epitomising ‘the common man’, appearing regularly as plumbers, teachers or honest policemen. He was the lead actor in Francesco Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (62), but later in his career he was more commonly to be found playing character roles in the likes of Margheriti’s Castle of Blood (Danza macabre, 64) and Tonino Valerii’s My Dear Killer (Mio caro assassino, 72)

Comments