Here’s an interview with Italian actor Franco Citti – who is famous for his work with Pasolini but also appeared in numerous other films – that I found on the web and have translated into English.

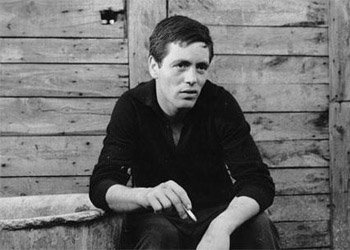

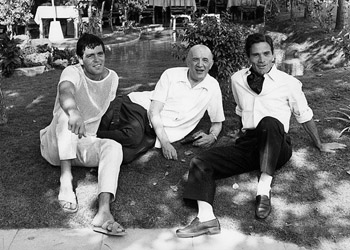

Fiumicino is cold and grey at dawn. Franco Citti walks along the shoreline exuding melancholy and gratitude. After twenty years of interviews with the protagonist of Accattone his memories are still not spent. The Roman actor tells a portrayal of Pasolini which is unusual: not a Pasolini who is an intellectual, but a friend…

“Look, my brother and I have said this a million times. It is absolutely impossible that his killer was Pelosi. He was a kilometer away from the massacre. And it was a massacre, those things couldn’t have been done by just one person. There are too many things that are unclear, hidden. And there’s also the politics, naturally.”

The voice of Franco Citti, the unmistakeable face of Pier Paolo Pasolini, is harsh and sharp. As are his thoughts, and everything else.

“I initially came from Rome because the Borgate were beginning to disappear, and with them my friends. And when they didn’t have their ho!es any more the people took shelter by the sea. And for this reason I came to live in Fiumicino. There is a sense of mortality, hereabouts, which gives me peace. Perhaps I am already dead, here, in this solitude that I love and that gives me joy. Or, rather, maybe I’m alive because I am in Fiumicino. Perhaps if I’d have stayed in Rome I’d already be dead.”

Q: How did you meet Pasolini?

Through my brother, Sergio, in a pizzeria of Torpignattara. Sergio said to me: “Brother, let me present a friend of mine, a writer.”

Q: You already knew of him, then?

No, in that period he wrote poetry in ‘friulano’, work from his early years.

Q: So you didn’t know exactly who he was?

No, initially I even thought that he was illiterate. He was a primary school teacher in Ponte Mammolo, my brother told me. I was all covered in lime because I worked as a mason with my father. Then after we met be began to see each other often.

Q: And what was your initial impression of Pasolini.

That he was a normal person. I didn’t think anything of the fact that he was a writer. At times I gave him some lines in Roman that he would use.

Q: So Pasolini put into his books stories that you and Sergio told him?

Paolo above all liked the spirit, the wag of the Roman Borgate, this man who was cheerful and true and who passed his time with us, in the borgate. And so, being someone who wrote by looking at the things that happened around him, he took things for outside and put them in his books. But what really interested me was when he said that he’d got a part for me in his film.

Q: How did you react?

You know, I’m a born pessimist, I don’t believe very much in the things that are offered to me. So I said to Paolo: “OK, good, when we do it we do it.” Then he said again: “There’s a great part for you.” And out of that Accattone was born.

Q: While you were shooting did you feel the part or was it something that you didn’t feel much connection with?

I felt at ease because I was shooting with all my friends from the borgate. We played around a bit.And then that adventure, that story, I liked doing it. For the film I also had to read Ragazzi di vita.

Q: And you shot it at Torpignattara?

Torpignattara, Il Pigneto, Testaccio, Pietralata. We went all around the peripheries of Rome. The film went on in this way for a while. He directed us, but we were free to be ourselves.

Q: So you had the opportunity to add some touches of your own?

You know, the dialogue was already partially written and Pier Paolo wrote it with my brother Sergio, but there were some line that in the dubbing felt better and we put them in. Accattone, though, remained as it was shot, and in fact it’s a good film because it was spontaneous, because it didn’t use professional actors and was made on the fly. And with restricted means. The people who were acting alongside me, and me as well, we didn’t come some mornings, they’d have things to do, they’d go off and do other things, and then it was a bit complicated.

Q: So there were problems that were practical rather than financial?

Financially there weren’t any problems. I believe that the film cost very little. I, for example, was paid eight thousand life per day. I worked for eight weeks, then more on the dubbing. You could say that I worked for about a year and I took home about the equivalent of a million and three hundred thousand more today.

Q: When you see yourself in Accattone what do you think?

I try not to see myself.

Q: Why?

Because now that film is a memory to me, as all the others, of the rest. At times they show Accattone on TV, and I also have the video, but I search for reasons not to watch it. Not because it’s old, but because I like watching it with the right people, with those who at the time challenged it, for example.

Q: How did Accattone change your life?

For the worse. You see, this relationship with Pasolini was for me, in a certain sense, destructive, because it wasn’t that I really loved doing cinema, but at the same time I know that I had to do it, perhaps if only put of friendship. And, as I’ve already said to you, in some ways it fascinated me, most particularly when I was working with my friends. But then I had to work with other people I didn’t know, and it broke my balls because they weren’t loyal to me. They were ambitious, you know? But then some people would say: “Well, that’s a borgataro”.

Q: What type of rapport did you have with Pasolini?

He was a little like a father to me. He had a great fear of me, that I could just disappear one day or another, without finishing the film. And then we did Mamma Roma with Mangani. I had a misadventure with the police, I argued with a policeman and they arrested me for insulting an officer; I did a sentence of around twenty days and then they let me out.

Q: The filming was interrupted because of this?

No, they used my brother’s shoulders as a kind of body double. And after that episode, when we did Oedipo re, Pasolini had no choice but to put a guard on the hotel to make sure I didn’t leave it. But, you know, for me the cinema was an amusement. It didn’t interest me much as a profession.

Q: If I’m not mistaken Pasolini has said that he simply wanted you to be yourself rather than to act…

Yes, it’s certainly true that he never wanted me to be French, English, American. But then I had a lot of requests. I did my third film with Marcel Carne, then I worked in America. I did two of the Godfather films with Coppola, the first and the third one.

Q: What significance do you think Pasolini has in today’s society?

He thought so many things which he told through his stories, his writings or his imaginings.

Q: So you think that many of the realities and tensions in his writing are still here in Italy today?

Yes, for sure. I think that if Pasolini was still alive the young people of today would be different to how they are. He would have loved them and would have taught them through his writing and his cinema. I’ve read very few of Pier Paolo’s things, but I knew him well and he was the most humane person I ever met. He was the father to all of us, us from the borgate, and he was very much loved. For us, he was he Baggio of the place, the person who would resolve everything. He gave charity to the poor, and as soon as he began to earn some lire he’d often go to eat, inviting everyone. He was a cheerful family. And I’m sure that it will remain like that for always, also for those who never read his work.

Q: What are the strongest feelings that you still have of him?

He left me with this feeling of a big war, an endless fight between people. But, I repeat, he was the most humane person I ever met. I’ve never met anyone else like him, someone who’d call out to the extras: Please, can you put yourself there. He had an extraordinary sweetness, and that’s what I remember most. He was like a father, you know? A guide along the right path.