1960

Original running length: 106 mins

Italy

A Moris Ergas production for La zebra film

Distributed by Cineriz

Director: Antonio Pietrangeli

Story: Ruggero Maccari, Ettore Scola, Antonio Pietrangeli

Screenplay: Antonio Pietrangeli, Tullio Pinelli, Ettore Scola, Ruggero Maccari

Cinematography: Armando Nannuzzi

Music: Piero Piccioni

Editor: Eraldo Da Roma

Art director: Luigi Scaccianoce

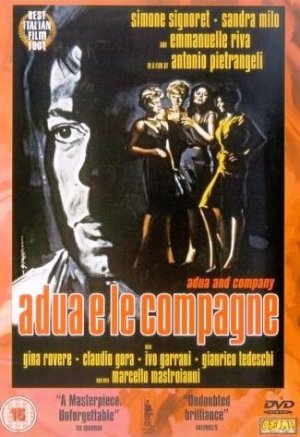

Cast: Simone Signoret (Adua Giovannetti), Sandra Milo (Lolita), Emmanuelle Riva (Marilina), Gina Rovere (Milly), Claudio Gora (Ercoli), Ivo Garrani (the sleazy lawyer), Gianrico Tedeschi (Stefano), Antonio Rais (Emilio), Duilio D’Amore (Brother Michele), Valeria Fabrizi (the blonde), Luciana Gilli (Dora, Piero’s girlfriend), Enzo Maggio (Calypso), Italia Marchesini, Michele Riccardini (a customer), Domenico Modugno (as himself), Marcello Mastroianni (Piero Silvagni), Nando Angelini, Roberto Meloni

Here’s a really very good example of the Italian new wave cinema that came out during the late fifties and early 60s, spearheaded by the likes of Pasolini and Bertolucci, and also including the likes of Mauro Bolognini, Elio Petri, Franco Rossi and Valerio Zurlini. It was a bountiful time for young Italian filmmakers; after a rather turgid period, distinguished by a succession of crowd-pleasing melodramas and ‘prestige’ releases from a steadily aging stable of directors, producers like Tonino Cervi, Franco Cristaldi and Goffredo Lombardo bought into the idea of investing in new talent.

Moris Ergas, the producer of Adua e la campagne, was a lesser known figure, who featured mainly in the press because of his long term relationship with the popular diva Sandra Milo, who also starred in many of his films. A Greek Jew who had been imprisoned in the Ferramonti Tarsia concentration camp during the war, he stayed behind after the fall of Mussolini and started out as a producer in the late 50s. He didn’t make a huge number of films, but among them were important titles by important filmmakers at the cusp of their careers: Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapò (59), Bolognini’s Senilità (62) and Tinto Brass’s Chi lavoro è perduto (63). Like them, Antonio Pietrangeli made films that both harked back to neo-realism but also had a more youthful, jazzy feel, echoing the contemporary feel that was beginning to infuse the popular cinema of the time, such as the spaghetti westerns and spy films. Although rather forgotten today, Pietrangeli was much respected in his time, with his The Visit (La visita, 63) and I Knew Her Well (Io la conoscevo bene, 65) proving particularly successful with the critics and, with its emphasis on characterisation and skilful writing, in many ways his work stands up better today than some of his contemporaries.

Following the implementation of the Merlin Law – which led to the shut down of all legalised brothels in Italy in 1958 – four prostitutes attempt to build a new life for themselves by setting up and running a trattoria on the outskirts of Rome. There’s Marilina (Emanuelle Riva), who is subject to fits of depression and has a son she hardly ever sees, the saucy, flighty Lolita (Sandra Milo), down to earth and maternal Milly (Gina Rovere) and their unofficial leader, Adua (Simone Signoret), the most businesslike of them and the main mover behind the project.

Things, however, don’t prove as simple as they thought: the trattoria is a wreck and without electricity; they’re quarrelling before they’ve even unpacked the furniture; and – despite a promise from the politicians that their past wouldn’t be held against them – they’re refused a license because of their police records. Adua is left with no choice but to go to a prominent local fixer, Ercoli (Claudio Gora), who agrees to buy the property for them and sort out the license… as long as they agree to receive guests who’ll be wanting more than just food and pay him a hefty monthly commission for the privilege. With the restaurant proving a thriving success and enjoying a series of burgeoning relationships, the women aren’t at all happy at the prospect of having to fulfil Ercoli’s demands.

This is an excellent film which, until it’s restoration in the early 200s, had been rather forgotten. Often described as neo-realist, it does have a neo-realist interest in everyday people and uses a lot of location shooting, but it’s also a very slick, accomplished production, with a cool jazzy soundtrack, great cinematography from Armando Nannuzzi (who also would also shoot The Visit) and a highly professional cast. The four main actresses acquit themselves very well, and while it’s Signoret who often gets the plaudits, special mention should also be made of Emanuelle Riva and Gina Rovere, a former singer and character actress, who are both excellent and bring great humanity to their characters. Marcello Mastroianni, something of a figurehead for Italian cinema of the time, has an amusing supporting role as a dodgy used car salesman, and popular singer Domenico Modugno pops up as a customer in the restaurant and even gets to sing a song. For fans of Italian exploitation cinema, there are early appearances from two familiar faces, Luciana Gilli (who was apparently sixteen at the time, and would go on to appear in several peplums and adventure films) and Fulvio Mingozzi, who had small roles in just about all of Dario Argento’s early films.

The script, by Pietrangeli, Ruggero Maccari, Tullio Pinelli and Ettore Scola, is very well constructed and the characters are expertly drawn. The protagonists are sympathetic, for sure, but they’re hardly paragons of virtue: the bicker, fight, make life generally difficult for themselves and have an assortment of unpalatable secrets in their pasts. But, despite the difficulty of their circumstances, there’s something cheering in the camaraderie they enjoy and in their fragile optimism they have, making this a surprisingly enjoyable – and often funny – film, despite the somewhat depressing subject matter (and the extremely bleak ending).

Pietrangeli, whose films often have a romantic, broadly optimistic feel, is also to be commended for ensuring that things don’t become as mawkish or melodramatic as they could do. The introduction of Marilina’s son, for instance, acts more as a way of drawing out the characters rather than acting as the cue for an outbreak of sentimentality, as happened so often in Italian films. And there are some wonderful scenes in their own right: a couple of con artists attempting to cheat money out of Lolita; Ercoli’s discovery that the women have little intention of servicing his clients, the opening bordello sequences. Highly recommended.

ADUA E LA CAMPAGNE

1960

Original running length: 106 mins

Italy

A Moris Ergas production for La zebra film

Distributed by Cineriz

Director: Antonio Pietrangeli

Story: Ruggero Maccari, Ettore Scola, Antonio Pietrangeli

Screenplay: Antonio Pietrangeli, Tullio Pinelli, Ettore Scola, Ruggero Maccari

Cinematography: Armando Nannuzzi

Music: Piero Piccioni

Editor: Eraldo Da Roma

Art director: Luigi Scaccianoce

Cast: Simone Signoret (Adua Giovannetti), Sandra Milo (Lolita), Emmanuelle Riva (Marilina), Gina Rovere (Milly), Claudio Gora (Ercoli), Ivo Garrani (the sleazy lawyer), Gianrico Tedeschi (Stefano), Antonio Rais (Emilio), Duilio D’Amore (Brother Michele), Valeria Fabrizi (the blonde), Luciana Gilli (Dora, Piero’s girlfriend), Enzo Maggio (Calypso), Italia Marchesini, Michele Riccardini (a customer), Domenico Modugno (as himself), Marcello Mastroianni (Piero Silvagni), Nando Angelini, Roberto Meloni

Here’s a really very good example of the Italian new wave cinema that came out during the late fifties and early 60s, spearheaded by the likes of Pasolini and Bertolucci, and also including the likes of Mauro Bolognini, Elio Petri, Franco Rossi and Valerio Zurlini. It was a bountiful time for young Italian filmmakers; after a rather turgid period, distinguished by a succession of crowd-pleasing melodramas and ‘prestige’ releases from a steadily aging stable of directors, producers like Tonino Cervi, Franco Cristaldi and Goffredo Lombardo bought into the idea of investing in new talent.

Moris Ergas, the producer of Adua e la campagne, was a lesser known figure, who featured mainly in the press because of his long term relationship with the popular diva Sandra Milo, who also starred in many of his films. A Greek Jew who had been imprisoned in the Ferramonti Tarsia concentration camp during the war, he stayed behind after the fall of Mussolini and started out as a producer in the late 50s. He didn’t make a huge number of films, but among them were important titles by important filmmakers at the cusp of their careers: Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapò (59), Bolognini’s Senilità (62) and Tinto Brass’s Chi lavoro è perduto (63). Like them, Antonio Pietrangeli made films that both harked back to neo-realism but also had a more youthful, jazzy feel, echoing the contemporary feel that was beginning to infuse the popular cinema of the time, such as the spaghetti westerns and spy films. Although rather forgotten today, Pietrangeli was much respected in his time, with his The Visit (La visita, 63) and I Knew Her Well (Io la conoscevo bene, 65) proving particularly successful with the critics and, with its emphasis on characterisation and skilful writing, in many ways his work stands up better today than some of his contemporaries.

Following the implementation of the Merlin Law – which led to the shut down of all legalised brothels in Italy in 1958 – four prostitutes attempt to build a new life for themselves by setting up and running a trattoria on the outskirts of Rome. There’s Marilina (Emanuelle Riva), who is subject to fits of depression and has a son she hardly ever sees, the saucy, flighty Lolita (Sandra Milo), down to earth and maternal Milly (Gina Rovere) and their unofficial leader, Adua (Simone Signoret), the most businesslike of them and the main mover behind the project.

Things, however, don’t prove as simple as they thought: the trattoria is a wreck and without electricity; they’re quarrelling before they’ve even unpacked the furniture; and – despite a promise from the politicians that their past wouldn’t be held against them – they’re refused a license because of their police records. Adua is left with no choice but to go to a prominent local fixer, Ercoli (Claudio Gora), who agrees to buy the property for them and sort out the license… as long as they agree to receive guests who’ll be wanting more than just food and pay him a hefty monthly commission for the privilege. With the restaurant proving a thriving success and enjoying a series of burgeoning relationships, the women aren’t at all happy at the prospect of having to fulfil Ercoli’s demands.

This is an excellent film which, until it’s restoration in the early 200s, had been rather forgotten. Often described as neo-realist, it does have a neo-realist interest in everyday people and uses a lot of location shooting, but it’s also a very slick, accomplished production, with a cool jazzy soundtrack, great cinematography from Armando Nannuzzi (who also would also shoot The Visit) and a highly professional cast. The four main actresses acquit themselves very well, and while it’s Signoret who often gets the plaudits, special mention should also be made of Emanuelle Riva and Gina Rovere, a former singer and character actress, who are both excellent and bring great humanity to their characters. Marcello Mastroianni, something of a figurehead for Italian cinema of the time, has an amusing supporting role as a dodgy used car salesman, and popular singer Domenico Modugno pops up as a customer in the restaurant and even gets to sing a song. For fans of Italian exploitation cinema, there are early appearances from two familiar faces, Luciana Gilli (who was apparently sixteen at the time, and would go on to appear in several peplums and adventure films) and Fulvio Mingozzi, who had small roles in just about all of Dario Argento’s early films.

The script, by Pietrangeli, Ruggero Maccari, Tullio Pinelli and Ettore Scola, is very well constructed and the characters are expertly drawn. The protagonists are sympathetic, for sure, but they’re hardly paragons of virtue: the bicker, fight, make life generally difficult for themselves and have an assortment of unpalatable secrets in their pasts. But, despite the difficulty of their circumstances, there’s something cheering in the camaraderie they enjoy and in their fragile optimism they have, making this a surprisingly enjoyable – and often funny – film, despite the somewhat depressing subject matter (and the extremely bleak ending).

Pietrangeli, whose films often have a romantic, broadly optimistic feel, is also to be commended for ensuring that things don’t become as mawkish or melodramatic as they could do. The introduction of Marilina’s son, for instance, acts more as a way of drawing out the characters rather than acting as the cue for an outbreak of sentimentality, as happened so often in Italian films. And there are some wonderful scenes in their own right: a couple of con artists attempting to cheat money out of Lolita; Ercoli’s discovery that the women have little intention of servicing his clients, the opening bordello sequences. Highly recommended.