Aka Dangerous Wives

Director: Luigi Comencini

Italy

Certification number / date: 28189 on the 21.11.58

First release date: 27/11/58

Production companies: Morino Film, Tempo Film (Milan).

Story: Edoardo Anton

Screenplay: Edoardo Anton, Luigi Comencini, Marcello Fondato, Ugo Guerra

Cinematography: Armando Nannuzzi

Music: Felice Montagnini

Editor: Nino Baragli

Art direction: Piero Filippone

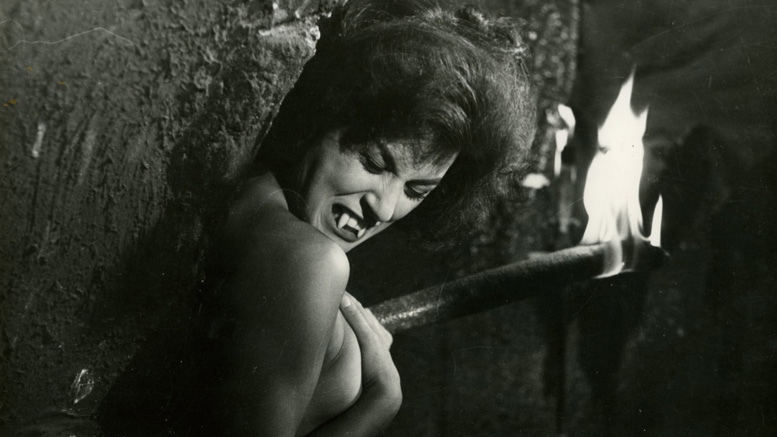

Cast: Sylva Koscina (Tosca), Renato Salvatori (Federico), Dorian Gray (Ornella, Bruno’s wife), Franco Fabrizi (Bruno), Mario Carotenuto (Benny), Pupella Maggio (Lolita, Benny’s wife), Pina Renzi (Ornella’s mother), Maria-Pia Casilio (Elisa, the pharmacist), Bruno Carotenuto (Tato, Benny’s son), Yvette Masson (blonde lady), Nando Bruno (the taxi driver), Vittorio Crispo (Caterina, the maid), Graziella Lonardi (Xenia), Nino Taranto (Pirro, Tosca’s husband), Giorgia Moll (Claudine, Federico’s wife), Rosalba Neri (Angelina), Mara Marilli, Pina Gallini, Riccardo Ricci, Silver Disy Bogino, Antonio D’Alessio

By 1958, Luigi Comencini was already a firmly established director with a long line of succesful, well made comedies to his name. Mogli pericolose was a kind of semi-sequel to his Marita in città, which was released to great acclaim the previous year. As well as reuniting a number of the cast members, it was also based on a story by Edoardo Anton, a respected figure in his field, and with additional input into the script by Tonino Guerra and Marcello Fondato, both of whom would go on to bigger things. Comencini obviously liked working with an established crew, with cinematographer Armando Nannuzzi and editor Nino Baragli – not to mention producer Massimo Patrizi – all returning from the previous film.

Pirro (Nino Taranto), an employee at a department store, goes on holiday with his young wife, Tosca (Sylva Koscina) and several friends: Bruno (Franco Fabrizi), Dr. Federico (Renato Salvatori), Benny (Mario Carotenuto) and their respective wives, Ornella (Dorian Gray), Claudine (Giorgia Moll) and Lolita (Pupella Maggio). While the men are out hunting, the women have a good gossip, and end up talking about marriage and fidelity. Ornella reckons that all males are naturally adulterous, while Claudine argues that her husband is entirely faithful. Unable to agree, the women decide to put Federico’s faithfulness to the test by having Tosca try her hardest to seduce him.

Back in Rome, the assorted couples experience a number of troubles. Bruno and Ornella have a huge fight over his repeated attempts to seduce other women, Benny becomes convinced that Bruno, who happens to be his boss, is trying to win Tosca’s affections and Benny and Lolita argue because, well, because they like arguing. Only Federico and Claudine seem to have a happy relationship, and even that begins to falls apart when she becomes convinced, quite wrongly, that he’s fallen for Tosca’s charms.

As with many of Comencini’s films – and, by extension, many Italian comedies – of the time, this is a gently probing examination of the concerns and mores of the emerging middle classes. It has a selection of likeable but human characters, played by a group of accomplished performers, and deals with subjects such as holidays, marriage, relationships and work, things that were uppermost in the minds of the target audience for this kind of stuff. It’s not disimilar, for instance, to La nipote sabella, which also starred Sylva Koscina and Renato Salvatori as a young couple (or pseudo-couple), or Il marito.

Decently made and technically proficient, it’s an accomplished film, but at the same time it isn’t really distinctive in any way. There were an awful lot of these middle-brow comedies made at the time, and a lot of them – despite being entertaining enough – amount to much of a muchness. As with many of them, it also shares the sense that it’s actually a fleshed out stage play. It doesn’t really feel, in other words, as though the writer has written with the medium of cinema in mind, unlike, say, Big Deal on Madonna Street, and it’s only really towards the end, as things reach a suitable farcical conclusion, that things become really cinematic.