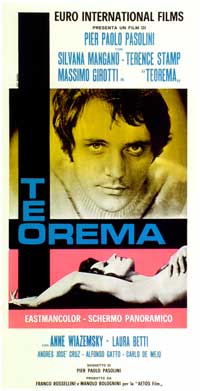

A Milan industrialist, Paolo (Massimo Girotti), has suddenly handed over his factory to the workers he employs there; the events are traced which led to this curious act of generosity. Not long previously a handsome young man (Terence Stamp) arrived unexpectedly to stay with Paolo and his family: the youth makes no particular demands upon his hosts but they all find him irresistibly attractive. It is their maid, Emilia (Laura Betti), who is the first to give way physically to his fascination after he has rescued her from a suicide attempt. Paolo’s son, Pietro (Andrés José Cruz Soublette), with whom he shares a room, is the next to offer himself, and again the guests response is a gentle, almost therapeutic acceptance. The industrialist’s wife, Lucia (Silvano Mangano), strips thoughtfully and lies in wait for the youth the following day, and soon after he also gratifies the desires of the daughter, Odetta (Anne Wiazemsky). Finally, it is Paolo’s turn to succumb during a car trip in the country. A telegram then arrives, summoning the guest away and he politely takes his leave of the family, despite the separate protests of each member that he has irreparably changed them. Emilia is again the first to react; she slips off to her home village where for days she sits in silence while peasants gather reverently around. A number of miracles occur, including levitation, and she is last seen buried up to her eyes preparing to weep a fountain of tears. Meanwhile, Odetta goes into a catatonic trance and is taken away on a stretcher, Pietro leaves home to carry abstract painting to extremes, and Lucia drives restlessly around seducing young men until she finds peace in a remote chapel. Paolo himself, his life in ruins, decides to give away his factory and then strips naked in a railway station, which vanishes into a desolate grey landscape across which he staggers, screaming and alone.

In the pre-credits sequence of Theorem, a reporter hectors the dazed recipients of Paolo’s factory, with the style of Godardian questioning that simultaneously supplies the required answers, into agreeing that no matter what the middle-class does it’s in the wrong. The joke is not simply one for Bertolucci and Bellocchio to enjoy, for Pasolini aims it at himself; his lifelong anti-bourgeois crusade having won for him a full measure of profit, he now perches with precarious irony on the fence between the vituperative ranks he once spoke for and the establishment comforts that irresistibly claim him. Not unnaturally, the result is neo-Moravian, a parable of dissipated integrity in which Marx and Christ… become interchangeable symbols of self-destruction. The trouble with gods is that they aren’t human; too easy, then, for them to demand the inhumanly possible. So Pasolini portrays the bourgeois family unit as if nothing could be more foreign to him than, for instance, to suggest to the whores of Rome that they form a trade union (Il gobbo) or to their pimps that money is a garbage commodity (Notte brava). True, the home is splendid to the point of being a palatial caricature, but within the breast of each family member beats a loneliness that Accattone would have been proud of.

A capitalistic yearning for true values? A portrayal of the characteristic bourgeois inability to avoid excesses of every kind, spiritual and physical alike? The film works both for and against its characters in an ambiguity that extends as far as the music on its soundtrack – a Mozart mass sung by a Russian choir. The reincarnation of Billy Budd invades them with a docile sexuality, they declare that this mirror of their desires has cured the blindness that kept them sane and they all go careering off the rails with varying degrees of despairing inventiveness.

One could leave it at that, if it were not that Pasolini gives too many strong signs of going with them. First, he is quite clearly find of the characters he has written: the maid who distractedly attempts to mow the lawn while her saviour coolly reads in his deckchair, the son through whose eyes we contemplate the piercing malaise of Francis Bacon, the daughter and her enormous snapshot albums (although Pasolini’s very choice of actress here is a simple enough guide to his feelings about the part [Anne Wiazemsky was married to Godard at the time]), the mother whose white, mask like face contorts with a terrible pain as she unwillingly picks up yet another man, and the father who is used for the last and most striking sequences of the film so that Pasolini’s identification appears complete.

Secondly, Theorem is punctuated by shots of bleak, volcanic dust, blowing almost subliminally across the narrative until everything is buried beneath an arid desert; flashing in, as it does, even while the guest is feeding the lusts of his disciples, the image spells despair throughout the film. And thirdly Theorem flicks its jaundiced observations (glibly, at times, but allegory does depend upon broadness of definition) across a full spectrum of social activity – political, sexual, artistic and religious – and finds nothing that can be trusted, nothing that endures. Even the godhead is carted away in a taxi, just as it once ascended into the clouds or became mutated through the words of Mao.

Yet, for all the depression, if this is indeed the Pasolini mood, Theorem is a film of extraordinary crystal beauty, in which Pasolini establishes himself as a master in the use of lighting and colour (the husband’s early morning wander is a hymn to both), as well as of landscape and architecture. Ambiguity aside, his scenes are crisp and unfussy: he has caught a number of Antonionian habits, possibly the most typical of which is the creation of compulsive cinema out of the tiny details of the narrative, such as Odetta’s choreographics on the grass, or Paolo’s long walk through the station. While his spokesman naked across a wilderness of demolished ideals, Pasolini has undoubtedly found in film-making a religion that affords at least a few compensations.

Philip Strick, Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1969

[One thing that struck me while reading this review was how Pasolini unconsciously initiated a whole subgenre: the ‘innocent arrives in middle class household and brings everone’s sexual frustrations to the surface’ type film. These were very popular throughout the 1970s, with Nello Rossati’s La nipote (74) and Mario Siciliano’s Erotic Family (80) springing to mind. In these film, though, there are some couple of big differences: the newcomer is almost always a nubile young woman; if homosexuality is often touched upon, it’s depicted in a ludicrously comic fashion; the emphasis is on having attractive performers – often Orchidea De Santis – disrobing as often as possible; and hardcore inserts were often added post-production in an attempt to make them more appealing to overseas markets. Quite what Pasolini would have made of all this I don’t know, but part of me thinks that he might have been tickled pink.]